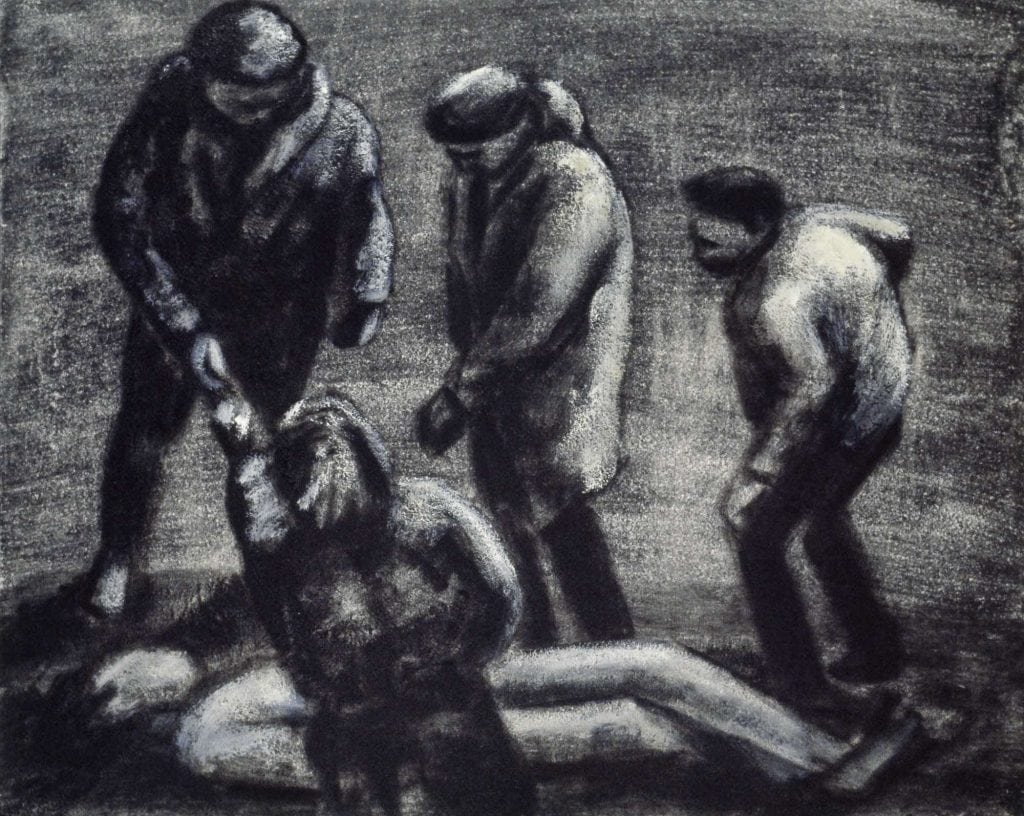

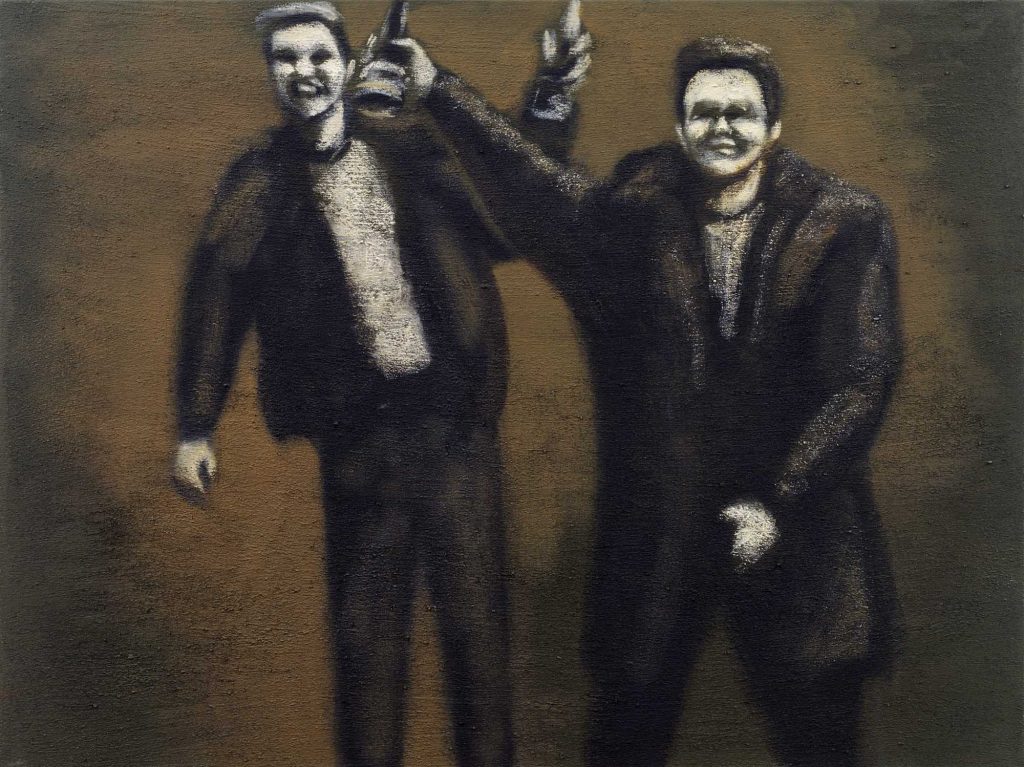

As an artist, Jane Dickson is compelled to witness, examine, and interpret. She works with the tools at hand, with observation and analysis distilled in paint. Figuration, her vehicle of expression, is flexible enough to accommodate either a narrative impulse or poetic metaphor. The figure invites projection and identification for artists and viewers alike. Dickson engages in translating the ecstasies and miseries of life within the man-made grid of the metropolis, revealing its effects on the body, psyche, and spirit. In her nocturnal views of a seedy Times Square, garish Las Vegas casinos, local carnivals, and commercial strip malls, she deploys a variety of rich color pigments on Astroturf, sandpaper, felt, and other culturally loaded support materials. Without flinching or missing a beat, she makes work that interferes with the homogenized business-as-usual narratives layered within the networks of mass media. Her art fearlessly hones in on our changing cultural landscapes, the unquestioned background room tone of daily life, and the relations between the shrinking public spaces of the street and the seemingly endless spheres of representation in the virtual web doppelganger.

“I paint what I fear: macho realms, Times Square, Las Vegas, strip clubs, demo derbies, highways, and garages; the unwelcoming, often dangerous, “man’s” world. The challenges of being a woman, operating in male domains where I rarely “belong,” agitating for respect and resources beyond what I’m usually offered, have shaped my personality and my work.”[i]

Rooted in the street as a site for public intervention, as a place to seek out alternative stories and ways of being, Dickson works with the existing repertory of cultural imagery and reveals the slippage or difference prompted in the interplay of power and illusion in contemporary America, particularly from a feminist perspective that has been ignored and erased from view. Rather than a smoothly polished verisimilitude or a crafted collage of fragments, Dickson’s rough-cut method often disorients, jars our senses, and doubles the vertigo induced by obliquely angled perspectives or alternatively, flattened peepholes and cubicles. She examines our appetites and capacities for collective and individual memory, spatial and psychic memory, and the politics and aesthetics of public space.

In college Dickson studied animation, and soon after her arrival in New York, she got a job working on the Spectacolor computer billboard above Times Square, the neighborhood where she worked on and off from 1978-2008. If New York City was considered “Sin City,” then Times Square was the deepest level of Dante’s Inferno, a den of predators and victims, pimps, perps, addicts, and hustlers. Dickson’s night-shift design job offered a clear-eyed view of urban noir; the brutal, neon-flecked architectural space compressing human desire and violence, testing each person’s capacity to absorb both wild fantasy and intensified reality.

By 1979, Dickson had become part of Colab (aka Collaborative Projects, Inc.), a radical collective of downtown New York artists, known for its ad hoc experimental art exhibitions that pushed the limits of artistic categories and launched graffiti and street art. Dickson and her peers became specialists in creating “guerrilla art exhibitions,” installed temporarily in non-commercial, non-institutional venues. Their nomadic exhibitions and events joined together neighborhoods and artists; they became engaged in the dynamics of activism, resistance, and negotiation, as well as in redefining a new art-of-the-street. In 1980 Dickson made her mark in The Times Square Show, Colab’s exhibition in an abandoned massage parlor, now considered a cultural landmark for its DIY multimedia mix of film, painting, dance, slide shows, music, 3-D works, prints, cartoons, and graffiti.

In this show at Howl! Happening gallery, Dickson’s paintings from the 1990s and 2000s reference the period right before Times Square’s blocks of concentrated desire, desperation, and vice were being gradually replaced by what the popular press called “Disneyfication.” Today the Disney flagship store—We can’t stop sprinkling the pixie dust![ii]—prominently resides in Times Square. Its clones create elaborate artificial environments—Main Street U.S.A.—designed to appear “absolutely realistic,” taking visitors’ imaginations to a past that is an illusion.[iii] This realistic looking fake makes it even more desirable for people to purchase the illusion as consumers. The system enables visitors to feel that technology and the created atmosphere of Disneyfication is “better” and more desirable than nature. Immersion in a hyperreal space like a Disneyland, a computer game, a home entertainment center, a movie, or a casino gives the subject the impression that she is walking through a fantasy world where everyone is playing the game.

Jane Dickson’s art has punctured the hermetically sealed game of games. As an artist, she was formed during the hybrid percolation of 1980s New York City. She developed critical insight into our increasingly media-saturated world and its effects on perception and desire. Key to bearing witness is the visual translation about what is often hidden from view within the systems of mass media and media streams. Dickson developed a studio practice, methodology, and lexicon to express what was nascent and not fully recognizable, and what at an accelerated pace is streaming from our ubiquitous array of smartphones, tablets, and other electronic gadgets to structure our psyches

[i] Jane Dickson, Casino Culture, Cultural Politics, Vol. 14, No. 3 (November 2018); 350.

[ii] See [Online]: https://www.inc.com/peter-economy/15-motivating-disney-quotes-that-will-inspire-your-success.html [Accessed December 2019]

[iii] Umberto Eco, Travels In Hyperreality (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986), 43.