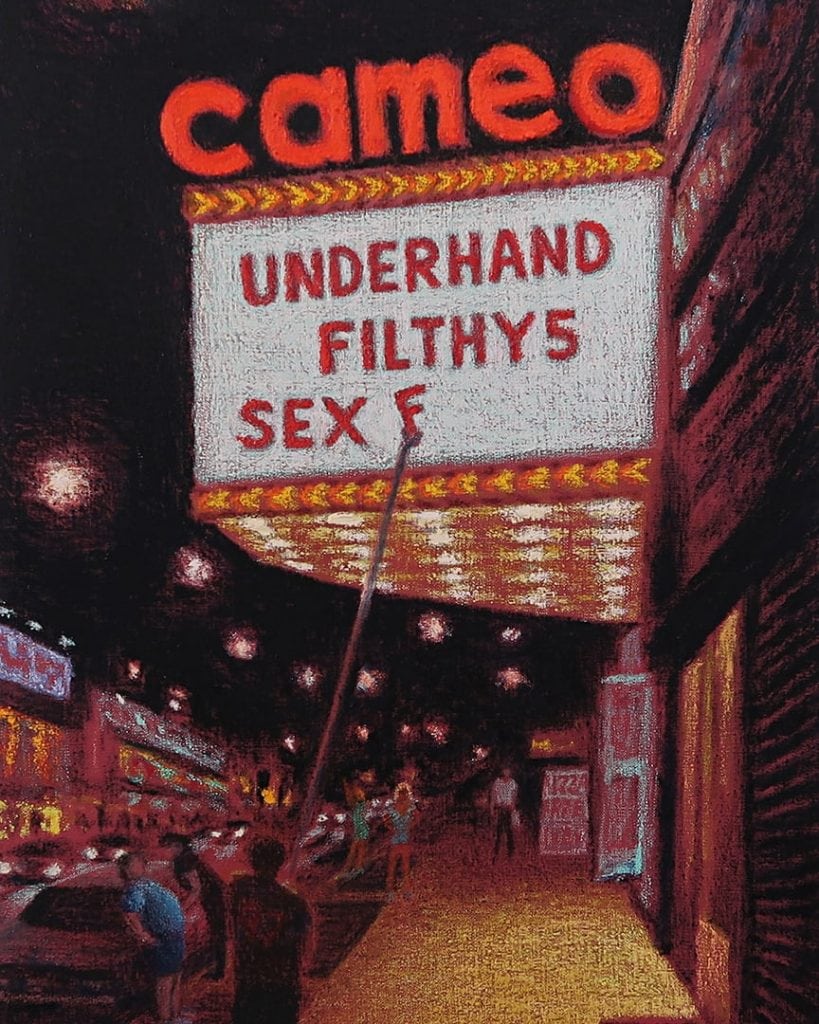

It was called the Tenderloin, not for any array of fancy steakhouses but because in a society of graft and corruption it offered the choicest cuts. Populated by pimps, prostitutes, chicken hawks, hustlers, and all manner of predators, Times Square, New York City, was in its way a kind of meat market, catering to a most wanton hunger like a craven fear of loneliness in which the crowds there danced to…a lost tune of collective solitude, a feeding frenzy of desire, a 24-7 repast of dubious satisfaction. And it was then, for its time, the paradigmatic commons, a public space in which the private is made indiscrete. This is where Jane Dickson lived and worked, where she raised a family and found her voice as a singular artist of America’s fever dream.

It is quite likely the sun shone upon Times Square as it does everywhere else, but we never saw it, nor does there seem to be much trace of daylight in Dickson’s paintings from that time. What the place promised was utterly nocturnal, made of neon glares and furtive shadows, never quite natural, just as artificial as the flesh it offered. This is the Deuce that resides in our collective memory still. Dickson, whose day job was a night shift, understood the dazzle as a kind of desire unto itself, what pierces the dark as it is enveloped by it, revelatory yet clandestine like the peep shows there that became her mimetic muse. Her employment as well was also in light, operating the legendary Spectacolor light board from a perch high above the news zipper at One Times Square, where she would program all the ads of this modern-day society of the spectacle, run the fabled New Year’s Eve countdown, as well as curate guest artist projects ranging from Keith Haring to Jenny Holzer that constituted some of the most seminal downtown to uptown cross-pollinations of the era. There she would leave the drab, dreary, and nasty world of this daytime demimonde, and as the sun set watch it come alive in a blazing neon glory.

Out of this light and darkness, this mad confluence of illumination, intoxication, and ignominy in that sunless carnal cavern, Jane Dickson crafted a new kind of chiaroscuro, as moody as Rembrandt, haunted as Goya, and perverse as Caravaggio, but never so much a play between contrasts as a bewildering bleeding of one into the other. This is the interstice of Dickson’s degenerate cityscape, never so much a dichotomy as a mutuality, the private intimacies of self subsumed in the guise of anonymity; the frisson of the flaneur lost in the crowd, the chance meeting, casual and coded, within the mix. Times Square represents the great crossroads of consumer capitalism and the city itself, where the human condition meets unseen forces and irresistible temptations in a betwixt that has had mythic meaning from hoodoo to the blues as a topography of liminality. And this is what this Sodom on the Hudson offered small-town, small-minded America: congregation in a zone of seemingly limitless possibility.

Jane Dickson has no illusions about the Deuce of yore, and would not propose her paintings as any kind of nostalgia. For her it was seedy, creepy, and dangerous, but it was also full of life and potential. It remains the last hegemonic disruption at a moment when the industrial and electronic eras slipped past one another, befitting Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the carnivalesque as that place hardwired into the human psyche where rationality and order are upended in the sensual. A young female out-of-town artist who landed in the middle of this mayhem, Jane recognized a pivotal time and place and how historic it actually was—not because it was sleazy but because it was indeed so wide open. Pre-AIDS and pre-gentrification it was the city socially untethered in the wee hours before the eventual lockdown. It was the kind of lie you could believe in, a two-bit con job hustle that only gained currency when you participated in it, and to this she brought rare witness from her own distinct vantage. And however Times Square may be viewed in the end, be it with desire or dread, in her paintings you can still feel the abject loneliness of the self amidst the rush and crush of the many. As society continues to get fragmented and separated, it is worthy here to remember this place for what it was, something like the graffiti scene that likewise inspired her: one of the singular sites where myriad difference converged across the usual boundaries of race, class, and sexuality.