Jane Dickson was just 25 when she arrived in New York in 1977. The following year she began working the weekend night shift as an animation designer operating the Spectacolor billboard at One Times Square—the first computer light board in New York City—bringing a woman’s perspective to a low-down dirty world.

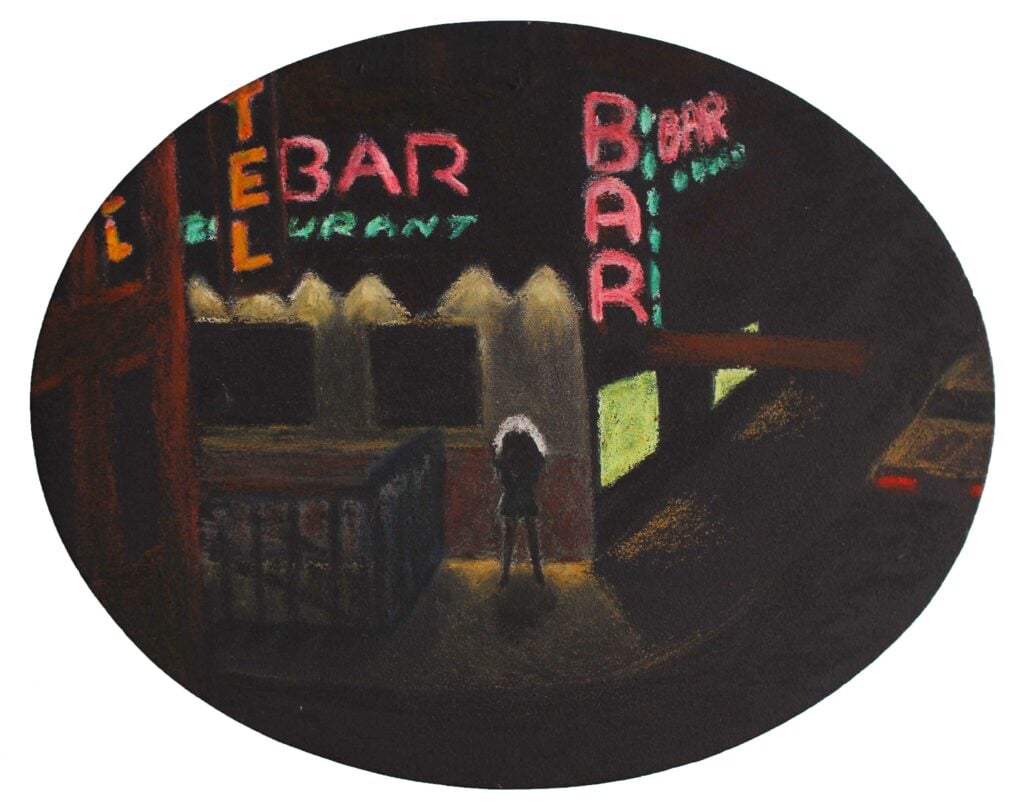

Times Square in the 1970s had become the red-light capital of the Eastern Seaboard. The Theater District offered a new kind of show happening at all hours, in and out of doors. Pimps, prostitutes, and hustlers walked the streets, peddling pleasures of the flesh. Strip clubs, XXX theaters, brothels, and sex shops lined the strip, catering to any peccadillo imaginable. The Great White Way had added a sequined thong to her sparkling tiara. As Broadway’s glitter turned to grit, Dickson became fascinated by the world in which she both worked and lived.

In 1981, she and husband Charlie Ahearn moved into a dilapidated building on the corner of 42nd Street and Eighth Avenue that they kept until 1992. Eager to capture her impressions of life, Dickson set up a studio around the corner with a view of the Peepland eye. Dickson later moved her studio to 39th and Ninth Avenue where she worked until 2008—her 30-year stint nothing short of a true New York marathon.

An observer of modern life among a sea of voyeurs, Dickson was drawn to the vibrant spectacle unfolding on the streets every day and night. Rather than offer a critique, Dickson tells it like it is. Her scenes of Times Square evoke the sublime wonder of a once grand empire reduced to rot, as voracious as it ever was. But the decadence of late capitalism as it played out on the Deuce was simply not enough.

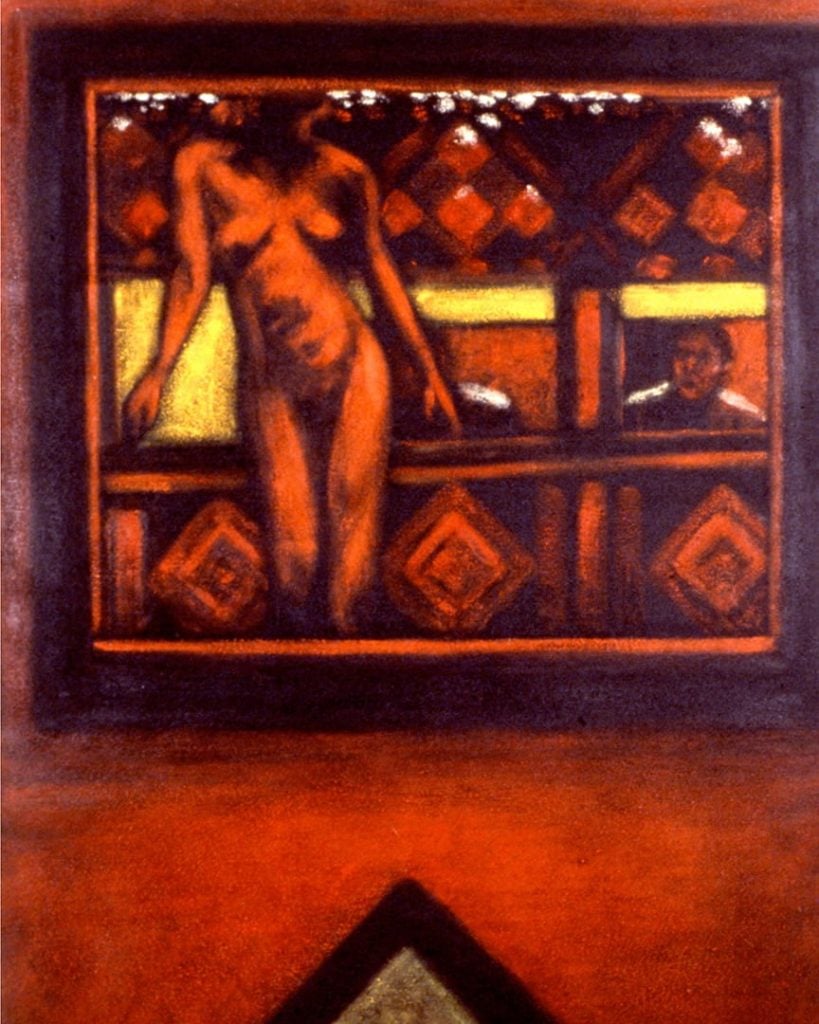

“I was observing my own life and challenging myself to make art about what I was witnessing and trying to figure out as a young woman,” Dickson says. “I realized that I can’t just paint signs and sidewalks. I needed to go inside the clubs.”

Jennifer Kabat, a Master’s candidate at Columbia University stripping her way through school, became Dickson’s model, confidant, and guide to the underworld that forbid unescorted women from entering clubs alone, lest they be a prostitute. Dickson went with Ahearn, who eventually bowed out. Then she began searching for others—an art dealer, a lawyer—to accompany her into a world designed to cater to the male gaze.

Behind the flashing neon lights and shiny facade, another truth awaited Dickson’s watchful eyes. Here, the war of the sexes played out in a dark, smoky club, with women of all shapes and sizes put on pedestals where they would play a heavily gendered role for tips. The mafia-run clubs were the epitome of the patriarchy, yet within this paradigm, subversion teased, tantalized, and transgressed Puritanical presumptions of morality about those who dared to strip.

Under the red lights, women transformed themselves into subject and object at the same time, using their agency to participate in a system that considered them expendable. But at a time before porn was ubiquitous, it was take what you can get: flat, saggy, untoned, untanned, unaugmented flesh. It was a job, but it was not professionalized. Instead it was a raw, unvarnished, naked display of power, desire, and need, locked in a timeless battle played out over and over again across the highly contested landscape of the female body.

“I felt like a woman hadn’t really documented this scene,” Dickson says. “It’s all about woman as object. So as woman as observer, which is my role, I am showing it the way it looks: less titillation and more grit. What I captured, particularly in the strippers is—they are working. They are beat. I felt like, I am doing a different kind of work in Times Square, but I am a working girl too. Like every woman, I perform.”