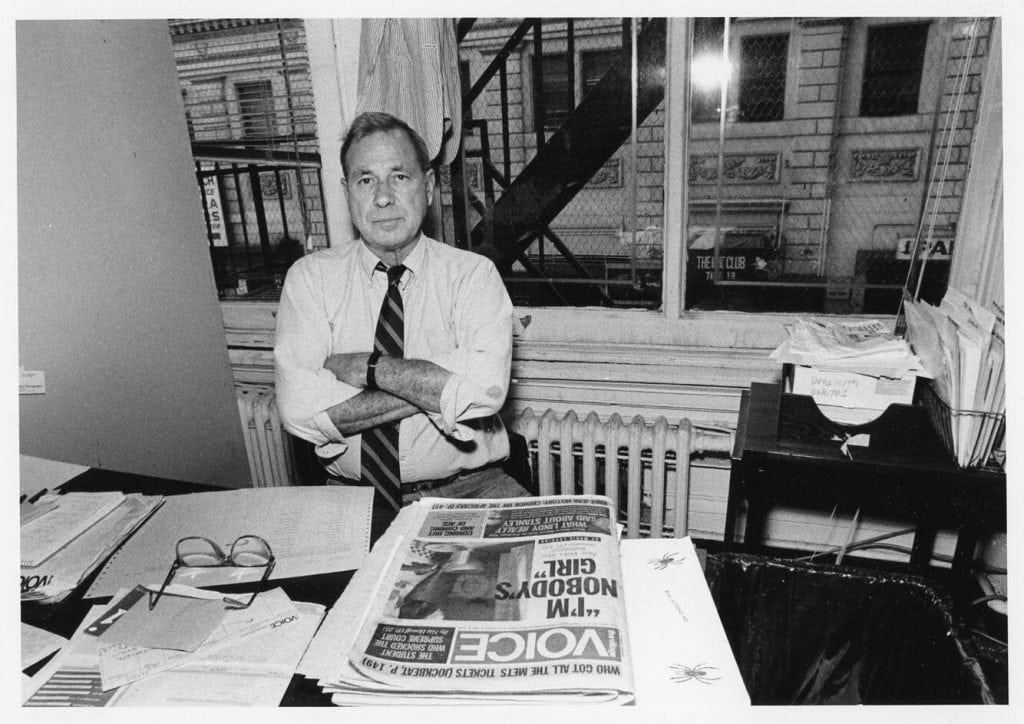

WHERE’S THE PICTURE? An Appreciation of Fred W. McDarrah by Tom McGovern

Fred was an old-school curmudgeon photographer and a first-class ballbuster. —Tom McGovern

Most of us in the Howl! family grew up with the Village Voice. It was our newspaper of record. It told us who was playing at what nightclub, the latest in the art world, fashion, social protest—just about everything we cared about was featured. So many artists, photographers, writers, and critics got their start there. And we didn’t just read the news, we scanned the photos. Here was our world, our friends, our heroes, our crushes, our tribe—pictured—creating the culture that defined era after era of downtown life.

So, it’s particularly fitting in light of Voice’s shuttering that Howl! presents a special 3-day exhibition (Oct 5-7) A McPhoto Family: Photography from the Village Voice that pays tribute to the contributions of the legendary Voice photographer/picture editor Fred W. McDarrah and more than 40 photographers he supported—a virtual platoon of talent.

Here follows an essay of Fred by Tom McGovern, one of the many great photographers Fred cultivated. Join Tom, his son Tim McDarrah, and the photographers for a reception on Sunday, Oct 7th, 4–6 PM. —The Howl! Team

Where’s the Picture? An Essay by Tom McGovern

That’s the famous line we all heard from Fred W. McDarrah, our boss and photo editor at The Village Voice.

Fred was an old-school curmudgeon photographer and a first-class ballbuster.

He had no artistic pretensions and didn’t really know how good his iconic pictures were until the late 80s, when galleries and museums starting calling. Asked once whether he had a style, he said, “I stand in front of something and take the picture—it either comes out or it doesn’t.”

He imparted—or more accurately, demanded—that same clarity of style and direct attitude from us photographers, many of whom started as interns. My internship lasted three months in 1988 and forever changed my photography and life. As a photo editor, Fred had absolutely no tolerance for excuses, hence the “Where’s the picture?” line we all got after rushing back to the office after a harrowing experience or missed opportunity. You knew you had to have something for the paper to run, and that pressure pushed each of us to ruthlessly pursue the image—or any image—whether a slumlord hiding his face behind a shoe (Marc Asnin) or a corrupt judge behind her umbrella (Linda Rosier).

My first assignment was to photograph a homeless camp at City Hall. When I got there, I was surrounded by some pretty angry men, one of whom was swinging a baseball bat. They demanded to see my Voice press card, which Fred had neglected to give me. I escaped unharmed but shaken and complained to Fred when I got back. You know what his reply was! And no, I did not have a picture.

The toughest assignments were those ‘stakeout’ photo shoots where you had to get a picture of someone who didn’t want to cooperate. Most of us dreaded those assignments, but we were also thrilled by the adrenaline rush of the hunt, near miss, and possible punch in the face. The reward was getting Fred’s grudging respect and acknowledgement you got the job done—this time—and having your picture and byline in the paper.

He also taught us we were only as good as our last picture. It didn’t matter how many successful assignments you had under your belt; one missed picture meant you were chewed out and told to find another profession. But this hot temper, while pretty unbearable to endure at the moment, also cooled very quickly. The next time you walked into the office or got his call, he’d be friendly and say you were the best person for the job. This trial by fire followed by his charming, paternal-like support made us tough, wary, and prepared for the next shoot.

As interns working the photo desk, we learned how to get pictures from other photographers and agencies, and how to negotiate a fee. Fred’s skills were formidable, and we could listen in when he was discussing the fee to charge for an image, when he would coyly say, “My usual fee is XX (always high). How does that sound to you?” He told us if you heard a gasp you could always come down, but if the fee was immediately accepted, you knew you had undercharged!

That was Classic McDarrah negotiation strategy, and he imparted this wisdom to us, even listening in when we were negotiating on the office phone, interrupting and prodding us to charge more.

A valuable lesson he taught us was how to read a story and identify the image-worthy elements (personality, place) and whether to either assign a photographer or find an image from a local photographer or newspaper. Fred developed an extensive list of photographers around the country who could be called upon, as well as a deep list of photo editors and agencies we would call for images and referrals.

Since Fred was legendary as well as infamous, cold calling other photographers could go either way. Some knew and respected him, so saying Fred sent you could open doors and get you the picture you needed for a good fee. Others hated him out of jealousy or from having suffered his tirades and wouldn’t sell you a picture for any price! Others loved to bust chops right back.

Jim Marshall, another famously crazy/volatile photographer, berated me when I asked to license his image of Johnny Cash flipping him off at San Quentin. Jim was ranting and raving about the Voice being a beatnik-commie rag and Fred being a cheap son of a bitch. After trading some insults back at him, he laughed and sent the print, which he later gave me as a gift.

Fred was combative in the office, too. Screaming matches with Wayne Barrett, Richard Goldstein and others created a tense atmosphere but established clear boundaries and lines of authority. Those matches were mostly pissing contests but also served notice not to mess with Fred or his crew. We felt emboldened, protected, and always under pressure to perform.

He told me that when he started at the Voice, he was selling ads during the day and taking pictures at night. He got $5 if his picture was published, so he was stingy with his film. He shot with a Rolleiflex camera that got 12 square exposures on a roll of film, and he might have Kerouac, Ginsburg, Warhol, and the Velvet Underground all on a single roll from that night’s prowl! He had a great instinct for what to shoot, the good sense to keep all his negatives, and the discipline to meticulously index them by personality, subject, and date. He understood that it was essential to know whom he photographed and quickly locate the picture to license.

This is a practice he taught all of us photographers and interns. Fred made us better photographers, toughened us for the rigors and competition of editorial and photojournalism, and provided us with opportunities no other publication did.

Working with Fred and getting your picture in the Voice was a badge of honor.