Most often the alchemy that produces a poem or a work of fiction is hidden within the work itself, if not embedded in the coiling ridges of the mind. —Patti Smith, Devotion[1]

Helen Oliver Adelson’s portrait paintings of her friends, family, and acquaintances seem to result from a kind of alchemical process. The sitter poses, always a single figure; the artist draws directly on the canvas, then paints the myriad elements: limbs, torso, facial features, eyes, hair, etc. In the process, she transforms the subject into something unique, an artwork as individual as the person she portrays, but with something extra, an additional spark. By means of line and color, Adelson intuitively unleashes and then contains a concentrated area of energy that she discovers within the character of each person, and which eventually resides in the completed portrait. The alchemy in Adelson’s work is thus hidden, embedded in the coiling ridges of the image as well as the viewer’s mind, a phenomenon that corresponds to the alchemy that writer and musician Patti Smith has observed in the creation of a poem or a work of fiction.

In Edgar Harlequin (2017), an approximately life-size image of her brother, Adelson shows the well-known writer and performance artist Edgar Oliver donning the checkered costume of a circus performer. It is an uncanny work, emblematic perhaps of the siblings’ close relationship. Raised by their artistic mother, they realized early on that they were very different from other children in Savannah, Georgia, where they grew up. Their mother taught them to celebrate that difference and encouraged them to become artists. The alchemical energy in Edgar Harlequin, with the figure shown from the waist up, radiates from the expressive hands and the mask-like rendering of the face. The elongated, twisted, and gnarled hands in particular convey an intense emotional power, as well as a certain psychological omnipotence that could reflect some aspect of her brother’s personality.

The intense focus on the hands in this work, combined with the rather formal pose of the subject recalls El Greco’s famous portrait, The Nobleman with His Hand on His Chest (ca. 1580), with its mysterious gesture. The anxious work-worn hands in Cézanne portraits, like Woman with a Cafetière (1895) or Seated Peasant (c. 1900-04), both in the Musée d’Orsay, also come to mind. The fantastically wrought, expressively exaggerated hands in other Adelson paintings, such as Gaby (2015), and David and Phillip (The Cat) (ca. 1990), are also key to the paintings’ psychological dimension. In David and Phillip (The Cat), it is difficult to turn away from the rhythmical, undulating hands in order to examine the demonic-looking cat that David caresses. These works beg comparison to certain Egon Schiele paintings and drawings. Adelson, however, has remarked that while she admires the Austrian painter’s works, they have not had a direct influence on her own. The subject’s hand in her Mimmo (2018), grasps a beverage-filled drinking glass. The elongated tubular digits here suggest rather phallic shapes and lend the painting a subtle erotic overtone.

The expressivity of Adelson’s paintings might appear to be part of a long tradition of psychological portraiture—from that of Otto Dix to Alice Neel. There is a humanistic quality to Adelson’s endeavor that she shares with those artists. A consistent ambiguity in Adelson’s work, however, sets it apart. The images vacillate between the hallucinatory, bordering on surrealism, and a raw pragmatic quality that makes them appear utterly truthful, despite the strange distortions. This singularity might best be observed in Adelson’s nude portraits.

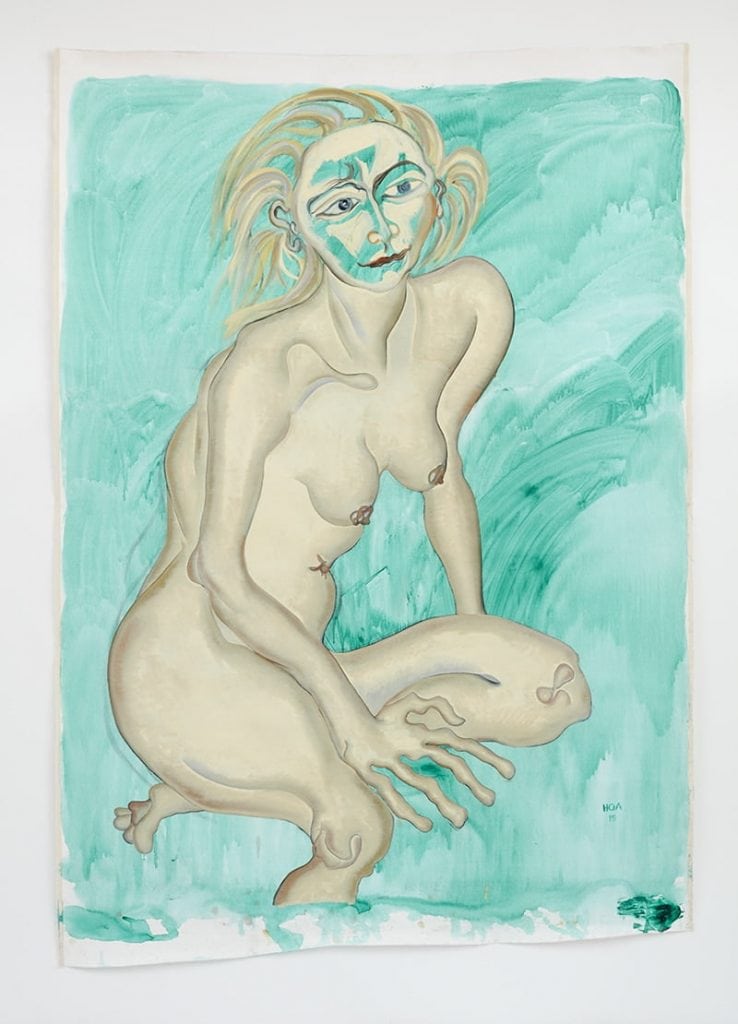

The female nude in a large 2015 composition, The Siren (Alex Wolkowicz), assumes a monumental presence, as the figure looms against a sumptuous turquoise background activated by bravura brushstrokes. The seated figure’s pale gray-white pallor might hint at a rather unhealthy physical state. The figure’s upright posture, however, and the firm musculature, with finely modulated shading of the coiling limbs, impart a lively tension. And the white face marked with thick turquoise lines, like a kabuki mask outlined with shocks of blond hair, also contribute to the work’s rather stylish and affirmative theatricality.

Similarly, a robust portrait of the artist Penny Arcade (1994), shows a reclining figure with a wildly exaggerated hand partially covering her left breast. The eye follows the serpentine lines of the right arm and torso upward, toward the face, which is marked with bright red lines. The tribal mask-like faces that are among the prominent attributes of Adelson’s portraiture reflect the artist’s aim to convey the sitter’s inner life, just as the eccentric features of the body she renders suggest an internal physiognomy rather than expected external appearances. In her practice, Adelson draws the figure directly on canvas while the sitter poses. She paints most of the canvas later, except for the face, which she always completes with the model present.

Adelson is largely self-taught as a painter, with a background in art history, specializing in Romanesque and Gothic art and architecture. She exudes in her artwork a profound sense of freedom to break the rules of conventional figurative painting. In one composition she can combine the graceful countenance of one of Graham Sutherland’s portraits, with the touches of lyrical grotesquery characteristic of a Francis Bacon portrait. Adelson’s work sparks a conversation about the metabolic implications of the body and body posture, as painter and sociobiology expert Desmond Morris explores in his 2019 book Postures: Body Language in Art. Examining portrait subjects as “power posers,” and noting a Harvard University study of the hormonal impact of posing for a portrait, he writes, “High-power posers experienced elevations in testosterone, decreases in cortisol, and increased feeling of power and tolerance for risk; low-power posers exhibited the opposite pattern.”[2]

Adelson likens the process of painting the figure to landscape painting, with strong emotional responses to line and color taking hold of her as the image evolves on the canvas. It is hardly surprising then, that she would find inspiration in the environs of Tarquinia, in Tuscany, Italy, where she lives and works for a large part of the year. The place is haunted by its ancient Etruscan culture, which lives on in its architectural remnants and in the phantasmagoric ancient mural paintings in the Etruscan tombs. The underground galleries are enlivened with ancient paintings that can be visited, and according to the artist, the murals’ rich, muted, earthy colors have informed her painting. Bomarzo Passageway (2017), for example, features a spare image of a monumental stone vault, and a road leading to a distant doorway, perhaps the entrance to a tomb. The work conveys the melancholy, elegiac air of the ancient city. Night Road from Mimmo’s (2018) and Lido Night Scene (2019) capture the hushed atmosphere and sense of enchanted reverie of ancient evenings. In her work, Adelson examines the possibilities of portraiture as highly charged psychosexual landscapes, and she lends to her landscapes and city scenes a personal, metaphysical dimension.

[1] Patti Smith, Devotion (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), 27.

[2] Desmond Morris, Postures: Body Language in Art (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2019), 70.