By Kelly Long

Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Museum of American Art

PhD Candidate, University of Rochester

I had a dream, once, as wild and as weird as the place from which Gail Thacker dispatches her Polaroid pictures. It was dark there too, but the darkness was tender, and not unsafe. There were characters I thought I knew: The Hermit, The Hanged Man, The Lovers, and Death. They were the gatekeepers of greater and lesser secrets, with unruly outlines that grew slack and began to drift before my eyes.

The mythology of Gail Thacker, the artist, begins with death, and it begins with a gift. The death was that of Mark Morrisroe, the photographer whose frenetic production was cut short when he succumbed to AIDS in 1989, at the age of thirty. The gift was also his: a box of Polaroid 665 Positive/Negative film, which he made to his friend, Thacker, shortly before he died. It was through the 665 negatives that time entered the picture, like a hungry stray through an open door. After photographing, Thacker set aside the unrinsed film—for days, weeks, years—and allowed time to have its hand in the work. It settled in, it created distortions: oil slicks in shades of pastel and neon; coronas, pitting the surface of the image; a scattering of starlight; haptic fizz. In some images, the world itself seems to buckle and dislodge. It is often difficult to guess where the hand of the artist ends, and time’s longer labor begins.

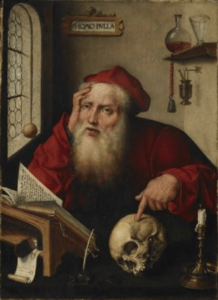

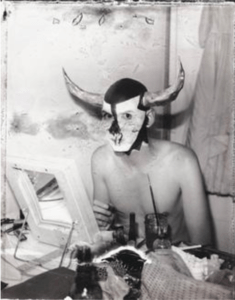

In 1997, Thacker took a photograph of Rafael Sánchez—another artist and co-conspirator—applying makeup before a production at Jackie 60 (the Meatpacking District’s most wayward gay nightclub of the 1990s). It bears an uncanny resemblance to Joos van Cleve’s 1528 painting of Saint Jerome in His Study (or any number of sixteenth-century Saint Jeromes, really). The priest’s inkwell and quill are doubled by Sánchez’s face paint and brushes; the Vulgate Bible on its wooden stand is matched by a tabletop mirror, from which Sánchez looks up to stare hotly into the camera’s eye. The vanitas skull to which the priest gestures is transposed upon Sánchez himself: his theatrical makeup and bull’s horns casting him somewhere between mischievous Puck and a devil, halfway done. HOMO BULLA (“man is a bubble”), the inscription hung on the back wall of the saint’s study, finds its correlate in the smattering of pinpoint dots across Sánchez’s dressing room wall and his painted face. The corruption is gentle—barely there—but it speaks. This place, this person, are time’s subjects too.

|

Saint Jerome in His Study (1528) |

|

Rafael Sánchez (1997) |

Writings on Thacker’s work have focused on their relationship to death, drawing parallels between the distortions created by time on the photograph’s surface and the human body’s inevitable decline. As Barbara P. Hitchcock remarked in an essay written upon the occasion of Thacker’s 2018 solo exhibition at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, “the decay of the Polaroid negative becomes a metaphor for our own mortality.” Jonathan David Katz foregrounded the work’s simultaneous incorporation and refusal of death, investing the photographs with the profound agency to “image their own dissolution,” while also positioning time as Thacker’s “co-author.” Thacker herself has claimed, about each photograph, “I manipulate it—I turn it into itself,” affirming both her own creative dexterity, and the work’s ongoing self-determination to become what it already is (or inevitably will be). This queering of the temporality supposed by the memento mori is not unrelated to postmodernism’s rejection of entropy and its objects, but it seems to have higher (or at least more human) stakes. Thacker, the friends and lovers she photographs, and time itself engage in world-building through these images, but theirs is a world that also exists before them—elsewhere, but proximate. Like death, like a dream.

Gail Thacker: Fugitive Moments exhibition catalogue launch will he held on Sunday 3rd February at Howl! Happening.